The luxury industry is broad – it encompasses everything from fine food and beverages to cars, aeroplanes, boats and fine art. Ultimately, luxury is down to one’s own definition; we all have different points where a “need” transitions into a “want”. Jithen Pillay looks at the subset of global players in the personal luxury goods market (leather goods, jewellery, apparel, shoes, etc.), and discusses whether there is an opportunity for valuation-oriented investors given the recent sell-off.

"The best things in life are free. The second-best things are very, very expensive." – Often attributed to Coco Chanel

Since the first civilisations, humankind has used material possessions as a signalling tool. Ancient Egyptians are arguably the most famous example, with the privileged building vast monuments to symbolise their wealth and power, fabricating precious metals and stones into jewellery to canonise significant events, using perfumes to deepen spiritual connections, and filling tombs with earthly luxuries for use in the afterlife.

Enduring traditions, a growing number of high-net-worth individuals and the emergence of the Chinese consumer have translated into robust growth in the personal luxury goods market …

Five thousand years later, little has changed. Expensive items are still used as an instrument of self-expression, as a visual symbol of achievement both to the person buying them and to others, and as gifts to mark special occasions – especially romantic ones. Today, we refer to the industry catering to this as “luxury” – a word that derives from the Latin for “excess” and “offensiveness”.

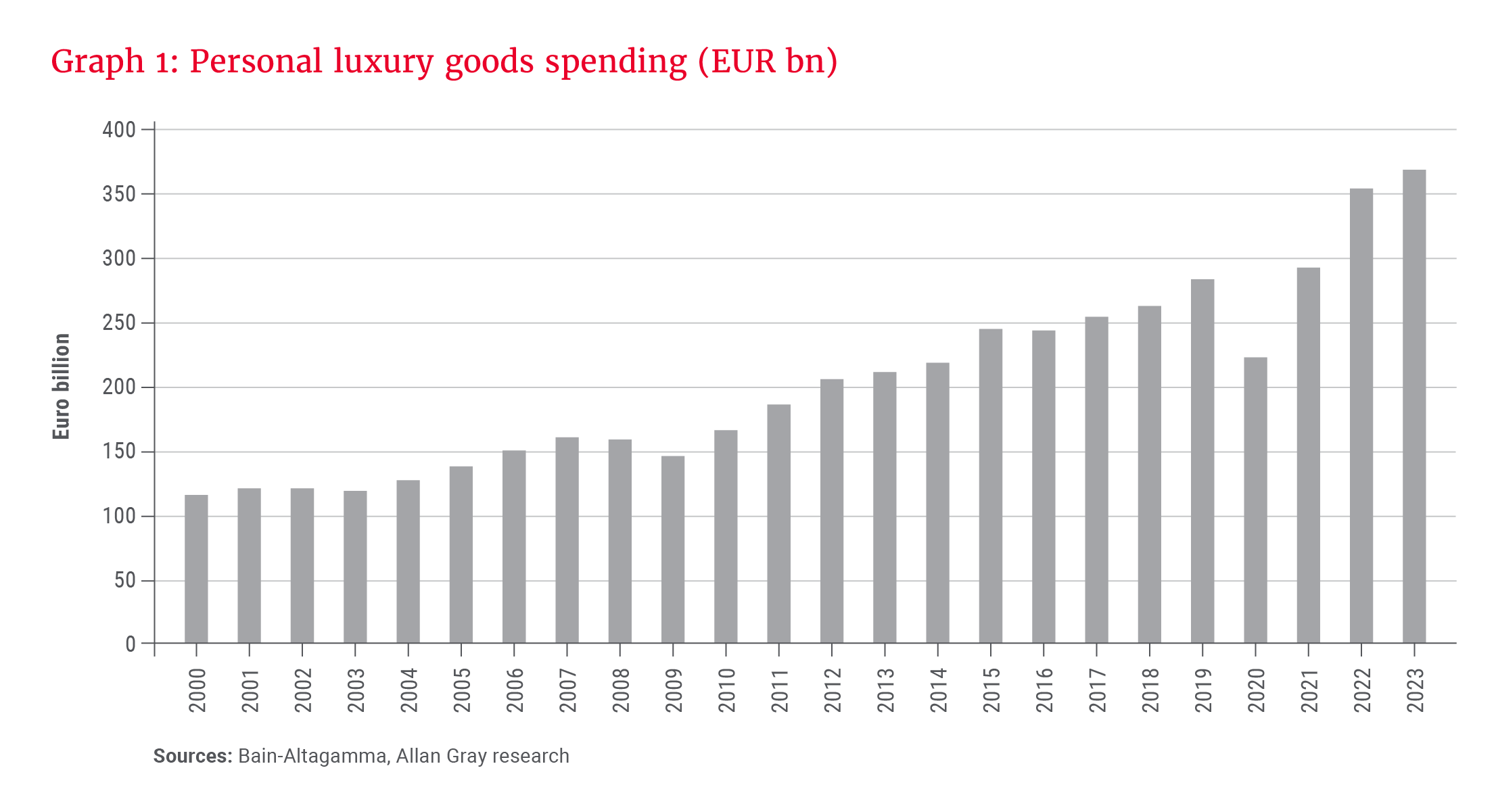

Enduring traditions, a growing number of high-net-worth individuals and the emergence of the Chinese consumer have translated into robust growth in the personal luxury goods market – from EUR116bn in 2000 to EUR369bn in 2023 (+5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR)), as shown in Graph 1.

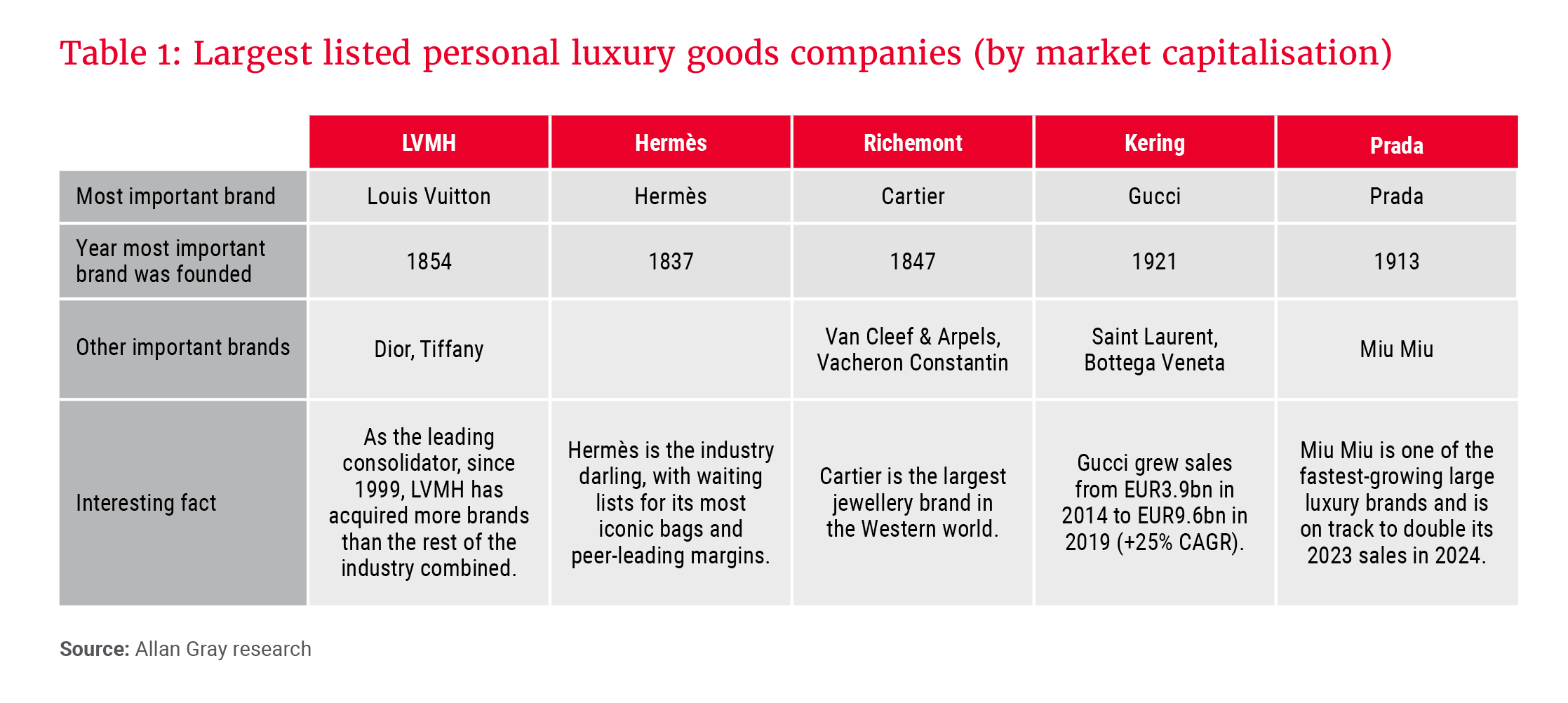

While the demand for luxury goods has endured, the companies serving these customers are vastly different from just 30 years ago. Largely through acquisition, the branded luxury industry has consolidated, creating a few mega-owners. The five largest listed personal luxury goods companies today (by market capitalisation) are shown in Table 1.

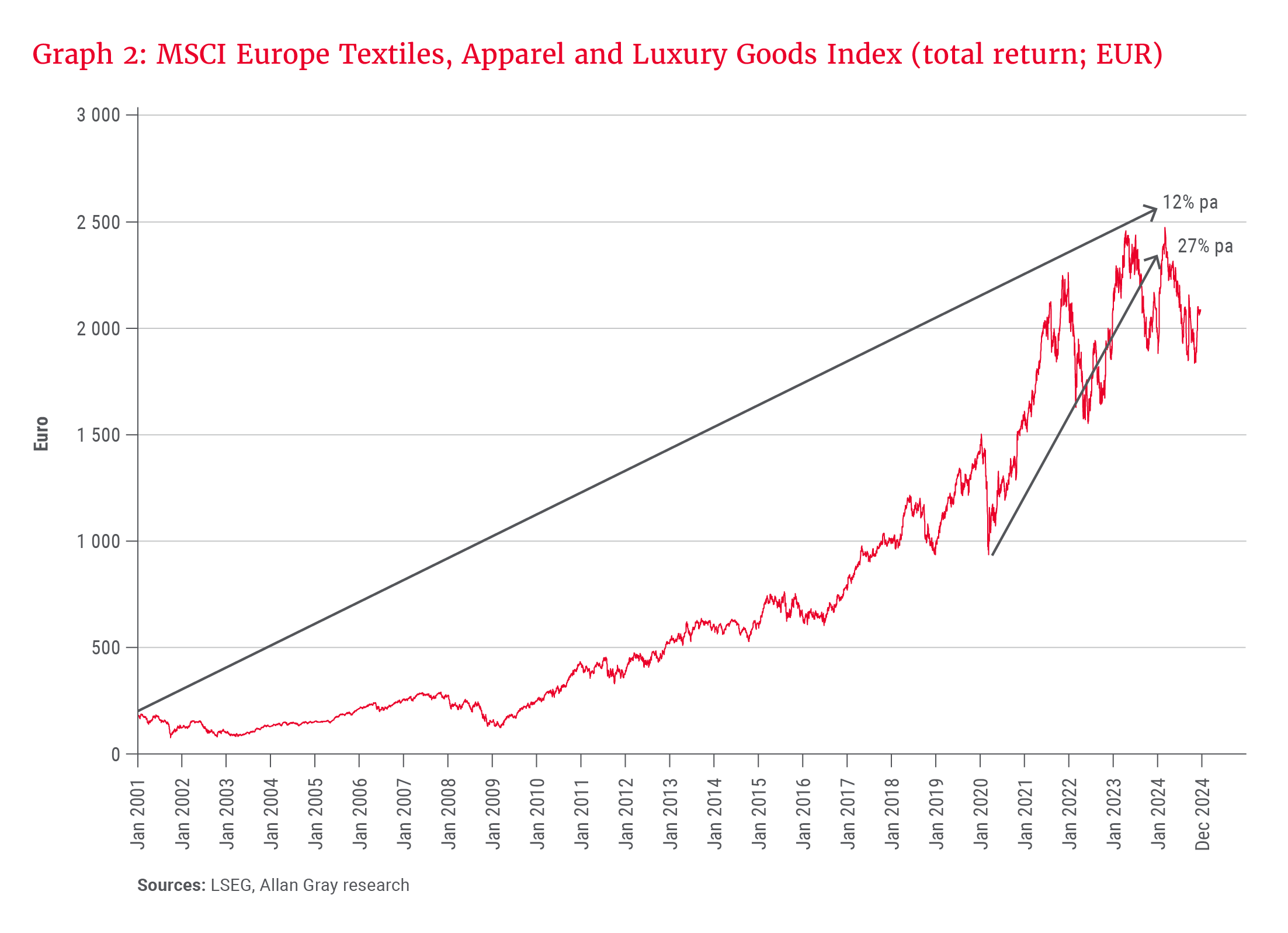

These luxury companies have yielded strong returns. Since January 2001 to the peak in March 2024, the MSCI Europe Textiles, Apparel and Luxury Goods Index, which includes almost all the names mentioned in Table 1, compounded total returns at 12% per annum in euros. This growth turbocharged during the COVID-19 pandemic: In the four years from March 2020 to March 2024, the index yielded a total CAGR of 27% in euros, as reflected in Graph 2.

Since the March 2024 peak, however, the index is down 16% to end-December 2024. Richemont, which has a secondary listing on the JSE, is down 20% in rands since its post-pandemic peak to the same end date. Such underperformance warrants a second look at the investment case.

The investment case for Richemont

There are several factors that make Richemont a high-quality business and a better business than it was a decade ago. These are outlined below.

Market growth

More than 50% of Richemont’s revenue comes from selling jewellery, with Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels being its biggest brands. The total luxury jewellery market grew at 9% CAGR in euros from 2008 to 2023. Growth here should continue through the cycle, driven by a gifting underpin (the majority of jewellery purchases) and a growing trend of self-purchases by women (supported by rising labour force participation in senior roles and a move towards female self-empowerment).

We have greater conviction in the longer-term outlook.

Branded players should fare even better: Jewellery is the only large luxury category where unbranded fabricators still command a high market share (60-70%). Unbranded jewellery is structurally losing share to branded jewellery, which is likely to continue as customers gravitate towards globally recognised designs.

Premiumisation

The hard luxury industry, which includes high-end, durable goods like jewellery and watches, is bifurcating, with ultrapremium brands outperforming as the high-net-worth consumer proves more resilient in tougher economic conditions. Cartier and Van Cleef are best placed to take advantage of this, given their positioning at the top end of the desirability pyramid. The brands are small enough to maintain exclusivity and premium pricing, but large enough to invest more than peers in client experience and marketing.

High barriers to entry

Provenance is important in luxury. Table 1 shows that the most successful luxury brands were established more than 100 years ago. The barriers to entry are even higher in hard luxury, given greater reliance on recognisable designs rather than logo identification. Iconic jewellery lines take decades to cement themselves into the psyche of consumers and are difficult to displace thereafter. Cartier’s popular Trinity ring was designed in 1924. Cartier’s Love bracelet, arguably the most recognisable jewellery piece in the world, was created in 1969.

Distribution

Of Richemont’s sales, 75% are made directly to the end-customer, either via its own stores or online – up from 46% in 2010. This is a function of the sales mix shifting towards jewellery (watches have a structurally higher wholesale component) and Richemont focusing its watch distribution on its most valuable third-party resellers.

The move to take greater control of the way its products are sold is a wise long-term strategy: It improves gross margins by cutting out the middleman, and in time increases operating margins by driving traffic via Richemont’s already-established direct retail network. Most importantly, it gives Richemont better control of its inventory. The latter is especially relevant in weak trading, to prevent wholesalers from flooding the market with discounted stock, which ultimately damages brand reputation and long-term pricing power. This is precisely what happened to Richemont’s Specialist Watchmakers division in 2017, following China’s graft crackdown.

Economics

Luxury companies exhibit favourable economics. Owing to steep prices and an increasing proportion of vertical integration, margins are high. Returns are also strong despite expensive store fit-out costs, given premises that are mostly leased. Working capital cycles, however, are much longer versus those of typical apparel retail. Balance sheets are also mostly run very conservatively; Richemont has almost EUR8bn of net cash.

… we are finding the Richemont investment proposition particularly interesting at present.

The recent sell-off in the luxury sector, however, is not without merit, considering the following factors:

-

Pandemic normalisation:Excess savings built up by US consumers during the pandemic (more than US$2tn at the peak), thanks to stimulus cheques and lockdowns that limited physical experiences, saw disproportionate spending on luxury goods. The revenue Richemont earned in 2024 from its Jewellery Maisons division is almost double what it was in 2021. It was inevitable that this rate of growth slowed as countries reopened.

-

Weaker demand from China: Chinese consumers comprise 30% of global luxury spending, and sales growth from the cluster has turned negative as a result of a weakening consumer.

As shown in Graph 1, luxury spend is cyclical and correlated with global macroeconomic factors. Even worse for Richemont, historically, hard luxury is more cyclical versus soft luxury (which includes fashion and accessories like leather goods and designer clothing). Richemont’s first-half financial year 2025 sales in Greater China are down 27%. -

Concern over US demand sustaining:Americans alone contributed one-third to global luxury spending growth from 2019 to 2023. This is not surprising, given their very strong economy, low unemployment, world-beating stock market, and household wealth that grew more than 50% over that four-year period.

Investors are naturally nervous about whether this resilience can endure. A global recession, geopolitical conflict, stock market crash and/or anything else that diminishes the consumer “feel-good” factor will negatively impact the luxury sector’s revenue and earnings. This was the case following the technology bubble bursting in the early 2000s, the global financial crisis in 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. -

Price versus volume: A classic model Cartier Love bracelet (in yellow gold) costs US$7 350 at the time of writing. If Richemont sells one of these in year 1, it must sell another to the same customer and one to a new customer in year 2 to register volume growth. This becomes increasingly difficult as each year passes, as Love bracelet penetration rises closer to its ceiling.

Some luxury brands have responded to this reality with aggressive price increases to compensate. This is good for short-term profits, but risks alienating the customer over the long term. Richemont has been more measured with its price increases compared to peers.

A long-term proposition?

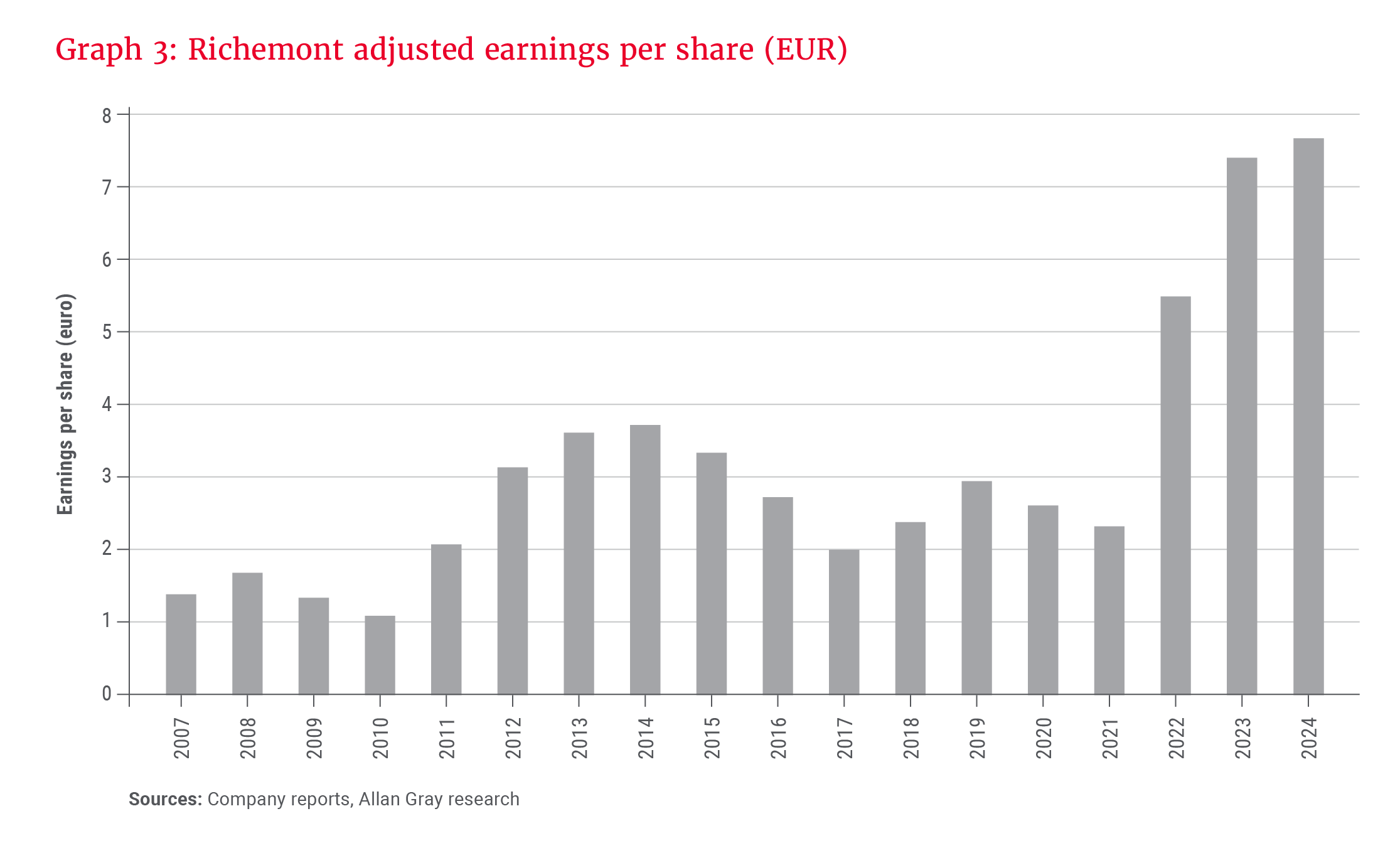

The luxury industry trades on 24 times trailing earnings; this is not overly expensive relative to its own history and relative to the through-the-cycle quality of these companies. Richemont trades on a similar multiple of trailing adjusted earnings. However, these earnings seem high compared to historic trends – as evident in Graph 3 – and near-term visibility is low given the headwinds discussed.

We have greater conviction in the longer-term outlook. The last time our clients were material Richemont shareholders was as the world emerged from the global financial crisis in 2009, when sentiment was low and market participants thought conspicuous consumption was forever dead. With the benefit of hindsight, this was the right time to buy.

While cautious, we are finding the Richemont investment proposition particularly interesting at present.

Explore more insights from our Q4 2024 Quarterly Commentary:

- 2024 Q4 Comments from the Chief Operating Officer by Mahesh Cooper

- Paying tribute to Gillian Gray by Craig Bodenstab

- Where investors fear to fish by Rory Kutisker-Jacobson

- Orbis: President’s letter 2024 by Adam R. Karr

- In safe hands with the Allan Gray Balanced Fund by Nick Curtin

- How to maximise tax benefits in a two-pot era by Carla Rossouw and Lee Kotze

- How to keep the lid on lifestyle creep by Twanji Kalula

To view our latest Quarterly Commentary or browse previous editions, click here.